Key Findings

- In July 1869, 7000 acres of the “Hempstead Plain” were purchased by Garden City’s Founder Alexander Turney Stewart for $395,328; The Hempstead Plain was the biggest private land purchase of the century.

- Stewart planned an entire town with his architect, John Kellum.

- Cornelia Clinch Stewart planned the most impressive buildings in GC: The Cathedral Complex and St. Paul’s School.

- After AT Stewart’s death in 1876, Cornelia continued to improve Garden City as a memorial to her beloved husband. NOTE: Mrs. Stewart accomplished all this before women had the right to vote!

- St. Paul’s is listed on The National Register of Historic Places.

- Designed by Henry G Harrison in the Ruskinian Gothic Style, a style rarely seen outside urban areas.

- In 2003 St. Paul’s main building was chosen by the Preservation League of New York State as “Seven to Save” significant but endangered properties.

- According to Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Goldberger, “St. Paul’s School is far more than a landmark in Garden City – it is one of the greatest works of the Gothic Revival in the United States along with the Cathedral of the Incarnation.

- St. Paul’s strengthens Garden City as a unique place with a unique history.

- See the in-depth report for the full details on the historical and architectural significance of St. Paul’s.

A Unique Planned Community

The news on July 17, 1869, that the multimillionaire “merchant prince” Alexander Turney Stewart had purchased 7000 acres of the Hempstead Plains came as a shock to the New York business world. The $395,328 paid in cash made it the biggest private land purchase of the century.

The enterprising Mr. Stewart eventually became known as one of the three richest men in the United States. An immigrant child from Northern Ireland, Stewart completed his classical education and briefly taught but soon chose to become a merchant in New York. Stewart became well known as a highly inventive and greatly successful merchant. Stewart built his “Great Iron Store”, the largest retail store in the world in 1862.

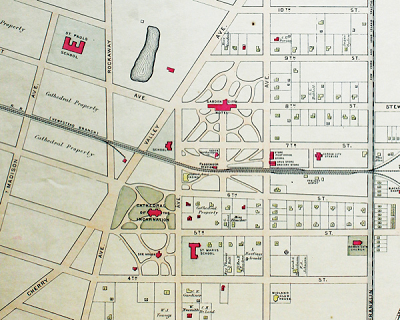

Once Stewart bought the massive Hempstead Plain property, he and his architect, John Kellum designed a master plan and mapped out wide streets and blocks for the nascent town of 500 acres. They designed a large park in the center, occupied by the Garden City Hotel, yet close enough to the Garden City Train Station for an easy commute to Manhattan. Thousands of trees and bushes were planted in the entire village at great cost to Stewart.

Stewart and Kellum planned everything a family might need for a comfortable, exclusive place to live: the streets connected to existing roads outside of town; lovely Victorian homes; a Water Works with a large well; a gas works, a few retail stores on Hilton; a railroad through the center of town with a station for commuters, mostly management who worked in Stewart’s store in Manhattan; stables downtown for horses and more. Nothing was left to chance with their careful designs and building restrictions.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a very widely read paper in all of New York City and its suburbs features an article written by Garden City real estate brokers and builders who teamed up to write this promotion on May 22, 1927, that reads in part:

“Garden City the Village Without a ‘Main Street.’ With its nation-wide reputation as the largest and most beautiful restricted home community in New York State, with its innumerable advantages, including all improvements such as water, sewers, gas, electricity, sidewalks, wide streets, street lighting and paving; extraordinary police and fire protection; low living costs and low taxes; famed boulevards; trees and beautiful planting; daily ash and refuse removal direct from cellar to truck; marvelous private and public schools; cathedral and churches; country clubs and golf links; school bus system; excellent train service to Manhattan and Brooklyn, with 60 trains daily, six railroad stations, electric service, low commutation rates, and average running time of 40 minutes; famous Garden City Hotel and recreational facilities; freedom from congestion with average plots nearly a quarter acre in size; accessibility to ocean and Sound; focal point for national sporting events; constantly increasing values- with all of this, GARDEN CITY has more to offer on a dollar basis than any other community in the State.

Of course, Garden City now has a “Main Street” to go with all the other amenities!

Cornelia wasn’t the traditional real estate developer. She did oversee the building of homes here, but her major accomplishment was the development of the most important, iconic set of buildings in Garden City: The Cathedral complex including the St Paul’s School.

Cornelia Mitchell Clinch was born in 1803. She was one of nine surviving children out of 24. The Clinch family attended a church in lower Manhattan where Cornelia met Alexander Turney Stewart. They married in 1823 and had two children, John (b.1834) and May (b.1838) but sadly, both died as babies.

Without small children to care for, Mrs. Stewart was a full partner in Garden City’s development with her husband, Alexander Turney Stewart, the retail genius. She was familiar with every aspect of its growth. As our country was entering the Gilded Age, Cornelia continued the grand vision they both had for our town, despite serious public doubt of its viability after he passed away in 1876.

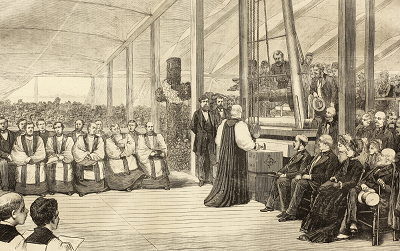

Without much time to mourn her husband, Mrs. Stewart set to work improving Garden City. Her glorious vision was a lasting memorial to her husband and a final resting place for both. Cornelia’s vision meant not only building the Cathedral, but also the See House (Bishop’s Residence), the Deanery, Cathedral School of St. Mary’s for the girls and Cathedral School of St. Paul’s for the boys.

Mrs. Stewart accomplished all her generous projects before women had the right to vote. Alexander Turney Stewart’s and Cornelia Clinch Stewart’s legacies live on, more than 150 years after their visionary planned community on the Hempstead Plains was founded.

A Rare Gem

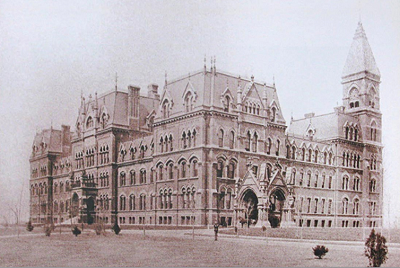

The Garden City entry in the AIA (American Institute of Architects) Architectural Guide to Nassau and Suffolk Counties describes the St. Paul’s Main Building as follows:

St. Paul’s School was from the outset an extraordinary structure. Designed by Henry G. Harrison in the Ruskinian Gothic Style, a mode rarely encountered outside of an urban context, the huge mansard-roofed brick building, with its ornate 300-foot facade, 500 rooms and fenestration comprised of 642 windows, was, on its completion, Long Island’s largest structure other than a resort hotel. Polychromatic voussoir-arched windows, elaborate cast-iron balustrades and Dorchester stone trim were some of the elements that combined to make St. Paul’s such a successful exercise in Victorian exuberance.

St. Paul’s School Main Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 as part of the A.T. Stewart Era Buildings district. The National Register of Historic Places is the Nation’s official list of cultural resources worthy of preservation.

In addition, in 2003, the Main Building was chosen by the Preservation League of New York State as one of its “Seven to Save” significant but endangered properties. St. Paul’s and the Cathedral are the only two remaining major buildings commissioned by Cornelia Stewart in the 1880’s that speak to our history and our cultural values.

“St. Paul’s School is far more than a landmark in Garden City—it is one of the great works of the Gothic Revival in the United States, and along with the Cathedral of the Incarnation it stands as one of the key buildings by the American architect John Kellum and the British architect Henry G. Harrison.

St. Paul’s is a monumental civic building in the very best sense in that it is a work of great architecture and like all great public architecture it inspires us with the potential of buildings to enhance the idea of community.

St. Paul’s strengthens the identity of Garden City as a unique place with a unique history. There is no doubt that the re-use of a building like St. Paul’s presents an enormous challenge, but it is also a great opportunity for Garden City to create a public facility that will be like none other anywhere, and that will make Garden City an even more special community than it is now.

I hope that citizens of Garden City can take comfort in the extraordinary success of the recent conversion of an even larger late-19th century complex at the other end of New York State, the enormous Buffalo State Hospital by Henry Hobson Richardson, which is being turned into a hotel, conference center and architecture center.

I’m confident that the restored and renewed St. Paul’s will be just as triumphant an example of adaptive reuse and will bring people to Garden City as the newly reconceived Richardson complex is bringing people to Buffalo.”

– Paul Goldberger

Paul Goldberger is the New School’s Joseph Urban Professor of Design and the former Architecture Critic for both The New Yorker and The New York Times where, in 1984, his architecture criticism was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Examples of Successful Adaptive Re-use Projects of Historic Structures

Universal Preservation Hall, Saratoga Springs, NY

UPH is a state of the art, year-round performing arts and community events venue located in the heart of downtown Saratoga Springs’

Built in 1871, the Universal Preservation Hall is a premier example of High Victorian Gothic architecture in the United States. The beautiful brick and sandstone building features two staircases leading to the main theatre, a balcony, stained-glass windows, and a massive bell tower.

Originally used for religious meetings, the Universal Preservation Hall has been renovated into a 13,000 square foot community and performing arts space. This one-of-a-kind venue includes three distinct areas:

The Chapel: Located on the main floor, the Chapel seats about 90 guests, and it is a great place for an on-site ceremony, such as a wedding.

The Community Room: The large Community Room on the main floor seats about 250 guests, and it is a 2,600 square foot room. The ceilings are 15 feet high, making it a great venue for social events or cocktail hours.

The Great Hall: The Great Hall is a 5,500 square foot room, making it the largest space in the building. Located on the second floor, it is commonly used for concerts and other events.

UB’s Hayes Hall, Buffalo, NY

From late-19th-century insane asylum to 21st-century architecture and planning education facility, iconic building has a unique story. It has been named to National Register of Historic Places.

It was constructed between 1874 and 1879 as the Department of the Insane for the Erie County Almshouse. Buffalo architect George Metzger was only about 17 when he designed the building, which was one of his first commissions.

From 2010 to 2015, Bergmann Associates, a Rochester-N.Y.-based architecture and engineering firm, oversaw the $43.9 million makeover.

The renovation of Hayes Hall combines a complete restoration of the building’s exterior — including more than 40 blocked or altered windows — a repointing of its limestone block façade, a new slate roof matched to its original, and fully rebuilt cupolas.

The reimagined interior features bright, day-lit open spaces, widened corridors and informal learning zones throughout the building.

Among the building’s signature spaces is a two-story atrium and entry gallery curated as a space for exhibits and public events. Open critique spaces and living-and-learning landscapes on the second and third floors provide informal gathering spaces with pinup-ready walls.

In fact, the entire building is designed as a canvas for the work of faculty and students. Swivel ceiling lights can turn a blank wall into formal exhibition space. A full-wall projection system in the atrium will cascade digitally curated exhibits for public display.

The renovation has also uncovered new spaces – most notably the fourth floor, which had been closed off for decades. To host studios and critique spaces, the reclaimed attic features exposed wooden trusses and skylights for natural light (and a stellar view of the restored Hayes Hall clock tower and cupolas).

The original two-story auditorium on the fourth floor has been converted into a 110-seat event hall and lecture space featuring arched windows and a restored curvilinear ceiling.

The building was also redesigned with an eye toward sustainability while preserving its historic charm. Hayes Hall is on track for “Gold” certification under the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system.

The Old Nassau County Court House, Garden City, New York

The Old Nassau County Courthouse, also known as the Nassau County Courthouse and the Historic Nassau County Courthouse, is an historic 2-story courthouse building. Designed by noted New York City architect William B Tubby in the Classical Revival style of architecture with a grand rotonda capped by a white dome. Then governor Theodore Roosevelt laid its cornerstone in 1900 and it was finished in 1901.

In 2002 the firm of John G. Waite Associates restored the dome to its former glory. Renovations continued until 2008,

Packer Collegiate Institute, Brooklyn Heights, NY

At an 1844 public meeting in the growing city of Brooklyn, a group of prominent citizens called for a new kind of school: one dedicated to the rigorous education of young women.

The Packer Collegiate Institute—continues to thrive and be a center of education in Brooklyn. Packer is now a coeducational school offering pre-K to twelve curriculums.